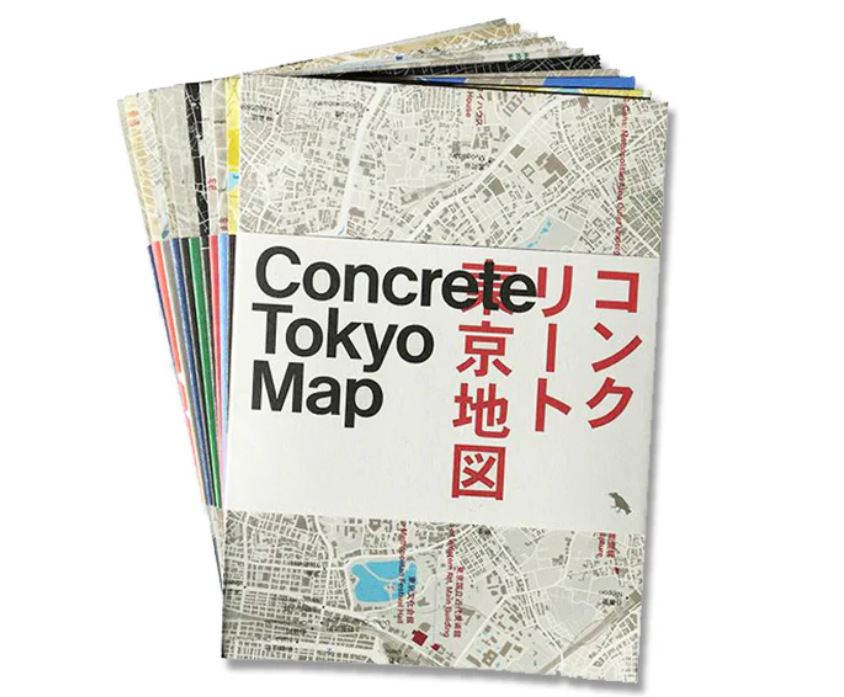

We’ve covered Blue Crow Media’s maps in the past, which focus primarily on modernist architecture (such as this roundup of cities from San Francisco to Tbilisi to Pyongyang) and also cover more specialist areas such as Berlin’s U-Bahn Stations. Here we take a look at four maps from their “Concrete” series, showcasing the wildly varied concrete forms of four cities.

Concrete Chicago Map

Chicago’s architectural landscape includes a wide array of Brutalist and concrete structures, ranging from iconic landmarks along the Riverwalk to lesser-known buildings in outlying neighborhoods. These structures reflect the city’s historical engagement with modernist design, offering a variety of civic, residential, and institutional examples that illustrate the medium’s adaptability in urban settings. The map highlights the breadth of these structures across both the city’s core and its outskirts, meaning that despite the city’s formidable spread, there should always be a landmark no more than a short drive or train ride away.

Highlights:

Marina City (Bertrand Goldberg, 1964): The twin “corn cob” towers along the Chicago River are one of the city’s most recognizable modernist landmarks.

University of Illinois Campus and Daley Library (Walter Netsch, 1960s): This Brutalist campus, including the Daley Library and other structures, illustrates the bold and functional aesthetic of midcentury academic architecture.

St. Mary of Nazareth Hospital Chapel (Edward Dart, 1968): A sculptural concrete gem that stands apart from Chicago’s more prominent modernist buildings.

Arthur J. Schmitt Academic Center (DePaul University, 1968): A modernist academic building demonstrating that Brutalist and concrete structures are not exclusive to UIC, offering a distinct presence within DePaul’s Lincoln Park campus.

Concrete New York Map

New York’s dense urban fabric includes numerous Brutalist and concrete structures that are not always immediately apparent. The city’s modernist buildings are often located within close proximity, but the city’s sheer architectural density means they can sometimes be easy to overlook. The map provides solid overview, showcasing the role of concrete in shaping municipal, institutional, and residential architecture in an otherwise glass-and-steel dominated skyline.

Highlights:

Ford Foundation Building (Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo, 1968): An influential modernist office structure with exposed concrete elements framing a lush interior garden, located in Midtown Manhattan.

Bronx Community College: A hub of Brutalist architecture, featuring multiple concrete buildings that exemplify the robust, functional forms of midcentury modern design in an academic setting.

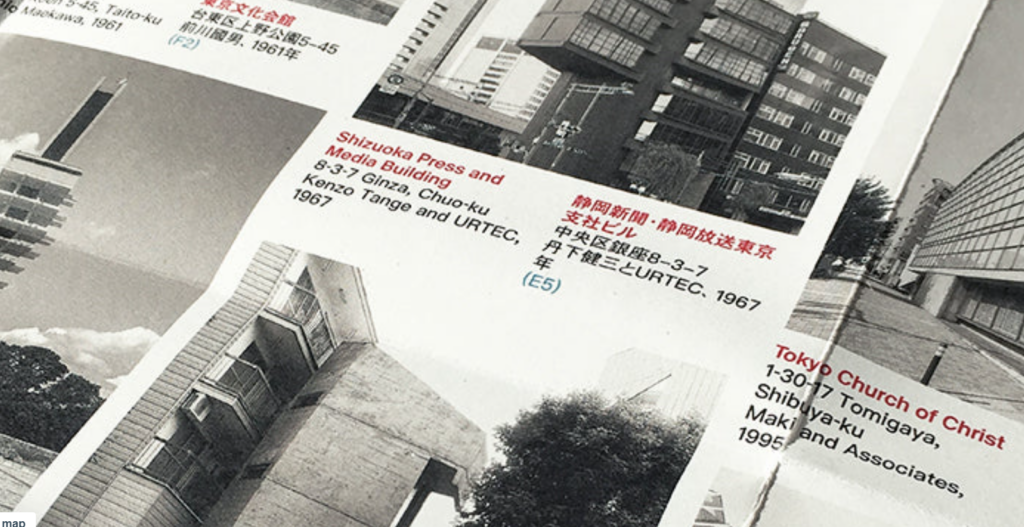

Concrete Tokyo Map

Tokyo’s concrete architecture demonstrates the material’s versatility in adapting to unconventional spaces and uneven terrains. The city’s modernist structures often emphasize innovative uses of form, incorporating spatial complexity and unique geometries. The map presents an overview of Tokyo’s architectural approaches to concrete construction, contextualizing its role within the city’s larger urban and aesthetic framework.

Highlights:

St. Mary’s Cathedral (Kenzo Tange, 1964): A modernist masterpiece with dramatic concrete folds and soaring verticality.

Yoyogi Stadium (Kenzo Tange, 1964): Another iconic structure from Kenzo Tange, this “viking longhouse in concrete” is known for its sweeping, tensile forms that blur the line between structure and sculpture. See our article on Yoyogi Stadium here.

Yoyogi Seminar Building (Kunio Maekawa, 1970s): An innovative educational space that highlights concrete’s flexibility in modernist architectural forms.

Concrete Seoul Map

Seoul’s modernist architecture is less widely recognized than that of other global cities, but its Brutalist and concrete structures contribute to its evolving urban identity. These buildings, which include cultural, civic, and residential examples, highlight the city’s adoption and reinterpretation of modernist principles during the city’s massive postwar growth. The map offers a focused look at these structures and their place in Seoul’s architectural history.

Highlights:

Eunpyeong Public Library (2015): A striking civic building that integrates geometric concrete forms with its surrounding environment.

Interrobang & The Closest Church (2014/15): Two standout examples of 21st-century concrete architecture that push modernist forms into a postmodern realm. Their innovative designs showcase concrete’s potential to create playful, sculptural, and thought-provoking spaces.

All maps available from Blue Crow Media.