IMMEDIATELY UPON ITS completion in 1970, Berlin’s Haus der Statistik (which stood north of Alexanderplatz in the shadow of the just-built Fernsehturm) took its place as one of the central organs of the GDR state apparatus. With the collection of data and statistics for all of East Germany as its goal, the eleven-story complex housed numerous bureaucratic units, including several floors of Stasi offices. Its street-level businesses were the ultimate in urbane GDR style, hosting two lounges (Jagdklause and the fabulously named Mocca-Eck), a hunting/fishing shop, and Natascha, a boutique offering the latest Soviet imports.

After reunification in 1990, the building housed the newly public center of all Stasi records, offering those it once observed and catalogued a chance to see what the state had had on them. As essential a function as this institution played in post-reunification Berlin, it occupied only a fraction of the immense complex, and by 2008 it had moved on, leaving the building entirely empty. In the following years, squatters, scavengers, and a range of urban wildlife (including pigeons and bats) transitioned through the building, along with graffiti artists, who covered the facade with tags and murals (including its most visible, the building-wide STOP WARS written in pseudo-Star Wars lettering). As the years stretched on, the building was sold, and, unsurprisingly earmarked for demolition and redevelopment.

Installing “ALLESANDERSPLATZ”. © Victoria Tomaschko

In September 2015, during Berlin Art Week, something new appeared on the building’s decaying facade. The artist collective AbBA (Alliance bedrohter Berlin Atelierhäuser) hung a banner declaring that a new project would soon be coming to the building: spaces for “cultural activities, education, and social projects.” It stated, with intentional ambiguity, that this transformation was either “supported by” or “demanded of” the city of Berlin (the German, “Gefordert von Land Berlin”, can mean either). The appearance of the banner was accompanied by speeches and a live, flashmob-style vocal performance, as well as various art actions throughout the week.

In the weeks and months after this initial act, an ongoing series of similar quasi-sanctioned art events played out in the space. The most visible, which still remains, is the installation Allesandersplatz, with bold white letters on the roof declaring the building something “altogether different” in a perfect play-on-words on nearby Alexanderplatz. With each new event, interest in the building as a potential future space for events, housing, and ateliers intensified. Eventually, in an only-in-Berlin twist, a half-decade after the initial action the declaration has become reality, with a wide coalition of artists and activists having convinced the city and various nonprofits to collectively save the building from demolition. Since then, this diverse coalition has forged ahead with a plan that, however tenuous, has nonetheless gained an aura of legitimacy, particularly since gaining the support of several key Berlin politicians.

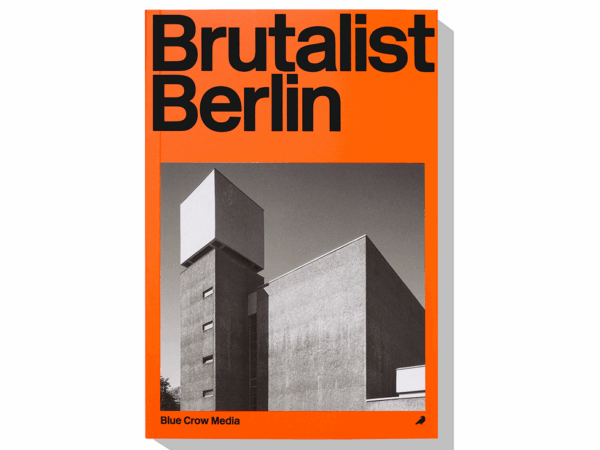

Statista: Towards a Statecraft of the Future documents this uniquely postmodern event while placing it in the broader landscape of post-unification Berlin. In essays and photos, the book situates the Statista project within various contexts: public art, housing and anti-gentrification activism, post-Mauerfall real estate speculation, and the simultaneously egalitarian and insular Berlin art world, to name a few. The book has a refreshingly clear-headed view of the numerous complex threads of history and art that converge in the Haus der Statistik, and doesn’t shy away from the uglier parts of either its past or its present – such as its history as a nerve center of GDR state surveillance for the former, and its position at the heart of a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood for the latter.

Were the project nothing more than a series of utopian manifestos, designating a massive abandoned building as an artistic site just for art’s sake, it would likely be (however noble its intentions) doomed to ephemerality. In bringing together a wide consortium of social scientists, housing advocates, historians, and local politicians, however, the project has gained a multi-columned stability it would otherwise lack.

The most interesting of the projects documented in the book go beyond humanistic utopian thought to include habitats for urban wildlife as part of the building’s long-term plans, including permanent nesting grounds for birds, bats, and bees. It’s not unheard of for high-concept modern buildings to propose spaces for flora or fauna, but opening up a 50-year-old building to such uses feels strangely radical. Such thinking reveals a truth often unspoken in modern environmental design: namely, that no new “green” building on such a scale will ever be as green as a building that has already been built.

raumlabor & Bernadette La Hengst, Voices – first recording, 2019-ongoing, neighborhood choir & handmade megaphones of various sizes © Victoria Tomaschko

Statista is a fascinating text: it’s part exhibition catalog, part manifesto, and part urban planning document, and is bound in a unique tall/narrow format that jibes perfectly with the book’s subject matter. That it centers around one of the most notorious and famous abandoned buildings in Berlin only adds to its appeal. Whether the overall project it documents will ultimately succeed remains to be seen, but even if it doesn’t, it serves as a lovely utopian coda to the singular history of the Haus der Statistik.

Statista: Towards a Statecraft of the Future

Edited by KW Institute for Contemporary Art and the ZK/U Centre for Art & Urbanism

Park Books

Text in English and German

€29.00

[…] John Peck of Degraded Orbit notes, the group stated the transformation was “gefordert von Land Berlin,” which can mean both […]