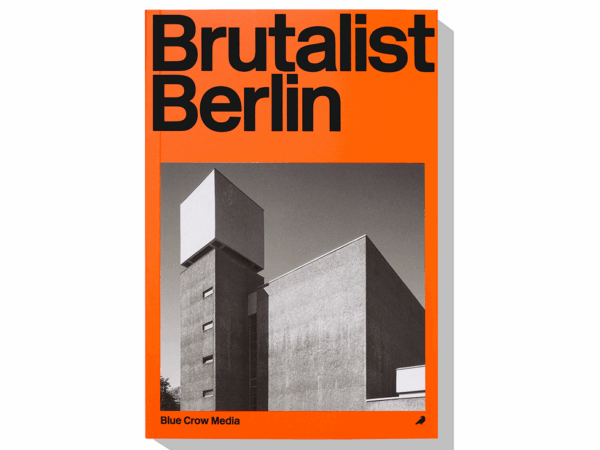

Unfinished Metropolis

DOM Publishers

750pp, 2 volumes in slipcase, € 48.00

THE GENESIS OF Berlin as we know it today happened just over a century ago, when, on October 1, 1920, the modern city of Greater Berlin (“Groß-Berlin”) was formed from eight adjacent cities and dozens of outlying districts. The formation of this new super-city doubled Berlin’s population from 1.9 million to what was, at the time, a staggering 3.9 million people, making it the world’s fifth-largest city after Tokyo.

While it is far from unusual to see major world cities expand and contract over time, as well as for the major cities of past eras to be overtaken by the new megacities of Asia, Africa, and South America, it is practically unheard of for a city on the scale of Berlin to be smaller in 2020 than it was 100 years before. The catastrophic destruction of WWII and the Battle of Berlin, which caused the population to plummet back to nearly its pre-Groß-Berlin level, also brought about the conditions that would keep the population low well into the following century. The crushing geopolitical gravity generated by Berlin’s position at the heart of the Cold War acted as a colossal reduction gear, stifling growth in both the Western and Eastern sectors of the city as each side threw all available resources into countering the advances of the other.

From our current viewpoint two decades into the 21st century and three into a reunified Germany, Greater Berlin’s first century appears as a repeating cycle of destruction and renewal. This cyclical progression informs both the subject matter and the overarching structure of Unfinished Metropolis, a monumental new 2-volume work from Berlin’s Dom Publishers. The book accompanies the exhibition of the same name (“Unvollendete Metropole”; info at end of article), and takes a many-faceted view of Berlin, starting with an examination of the newly-unified Groß-Berlin, a unification that only happened, unsurprisingly (and much like the BER Airport debacle of the 21st century) after decades of conflict and barely-there consensus. As the introduction points out, Greater Berlin has spent the majority of its existence outside of democratic rule:

Greater Berlin was not ruled by democratically elected governments for many years of its history. It was only governed democratically in the period from 1920 to 1933 and then again more recently since 1990. The Greater Berlin project has suffered many setbacks. The city is an incomplete project.

The rest of the book takes this idea to heart, and views Berlin through numerous lenses of becoming, rather than of being. Its perspective zooms out, for example, for dictator’s-eye view of the Nazi fantasia of Germania and the massive Socialist project Stalinallee. In a remarkable cartoon that compresses the curvature of the earth from Rome through Dresden and Berlin and beyond, reminiscent of Saul Steinberg’s “View of the World from 9th Avenue”, it even cast the Axis of WWII phantasmagorically onto the curvature of the earth. More frequently, though, its perspective zooms in on a staggering array of Berlin neighborhoods and city centers (Berlin’s paradoxical nature as a city with numerous “centers” is a recurring theme in the book), from lasting “centers” like Alexanderplatz and Zoologischer Garten to outlying districts like Friedenau in the West and Marzahn in the East, as well as yet more microscopic examinations of plazas, parks, and even specific artworks.

Unsurprisingly, maps are fundamental to the book, which features countless versions of the mapped city: street maps, transit maps, agricultural maps, Cold War maps from both East and West, comical maps by political cartoonists, utopian maps from the 1960s and 1970s, maps of neighborhoods long destroyed by war and property speculation, maps of futures that never came to pass. While such a vast array of maps might seem overwhelming, their overall effect is, paradoxically, one of greater focus. The accumulation of so many varied views of the city leads to a surprisingly unified view of the whole, like a cubist painting or a musical composition with a repeating theme. Berlin has spent the past century proving itself to be one of the world’s most unmappable cities (from a conventional perspective), with monumental buildings constructed and razed to the ground within decades – and, in the case of the Stadtschloß, built up again. The city has seen whole neighborhoods built, destroyed, and rebuilt, streets changing names from decade to decade, and of course its 30-year stint as two divided cities.

The accumulation of so many varied views of the city leads to a surprisingly unified view of the whole, like a cubist painting or a musical composition with a repeating theme

True to its cyclical take on Berlin’s history, the book favors a thematic progression over a chronological one, moving backwards and forwards in history, from the 1920s (and even earlier) right up to bleeding-edge current events like COVID-19, the new BER Airport, and the still-under-construction Tesla Gigafactory. While current mayor Michael Müller provides an introductory text, the true “host” of the book is Gustav Böß, mayor of Greater Berlin from 1921 to 1929. Böß possesses not only a far-reaching futurism – “Urban development should never be driven by current needs, but rather by how it will meet future needs” – but also a timeless weariness appropriate to anyone who has attempted to obtain a consensus in the cranky, contentious politics of Berlin. His words written in the 1920s resonate prophetically over the next century’s worth of maps, documents, and photographs, and introduce each major new thematic section, from Berlin’s rail network to its roads and streets to the issue of its numerous “centers”.

Fittingly, for a project so open to moving forward and backward in time, the second volume sets its eyes on the next half-century. This companion volume documents the “International Urban Planning Competition for Berlin-Brandenburg 2070”, where competitors sought to present comprehensive visions for the next 50 years. The competition, as well as Volume Two itself, take an international view of city planning, looking abroad to other European capitals from London to Paris to Moscow. The text offers ample historical context for each city covered, ultimately highlighting the ways in which Berlin’s challenges are either different from – or, more frequently, surprisingly similar to – those of other cities.

Unfinished Metropolis provides many useful lenses through which Berlin’s often haphazard, unfinished, and imperfect urban systems can be viewed. Its willingness to travel quickly between past and future makes for a highly readable text, which nonetheless remains grounded in reality. Most importantly, it shows Berlin’s resilience in outliving adversity. The shadows of a global pandemic and an imperiled EU may still be looming, but Berlin has seen more than its share of challenges over the past century, none of which have broken its capacity for self-reinvention.

The exhibition “Unvollendete Metropole: 100 Jahre Städtebau für Groß-Berlin” runs at Kronprinzenpalais through January 3, 2021.