TXL. Berlin Tegel Airport

Park Books, € 38,00 (hardcover), English / German

248 pages, 232 illustrations

BY THE TIME Tegel Airport officially opened in 1974, Berlin had already seen more than its share of aviation history. Half a century earlier, Otto Lilienthal launched his innovative gliders from a hilltop in Lichterfelde, and throughout the Weimar years and into WWII and the Cold War airfields sprung up all over the city.

To mitigate the relentless strain placed on the then-primary Tempelhof Airport by the Berlin Airlift of 1948-49, a series of airstrips were hastily constructed at the edge of Jungfernheide Forst in the northwestern French sector, and they soon served as the primary air base of the French military in the city. Starting in 1960, Air France used the small terminal north of the runways to launch its passenger service, beginning what would become its six-decade history at the site.

All images © Park Books, used with permission

As Berlin entered the 1960s, Tegel’s increasing importance (alongside Tempelhof, still the city’s central airport) dictated the urgent need for a new terminal that could handle passenger numbers in the millions annually. In 1965, a contest for the design of this new terminal saw entries from dozens of internationally-recognized architectural firms. The winning design came not from one of these companies, but rather from a young team out of Hamburg whose cohorts were barely out of college: Meinhard von Gerkan, Volkwin Marg, and Klaus Nickels, who would soon become Von Gerkan, Marg and Partners and bring their unique vision for Berlin’s new airport to life.

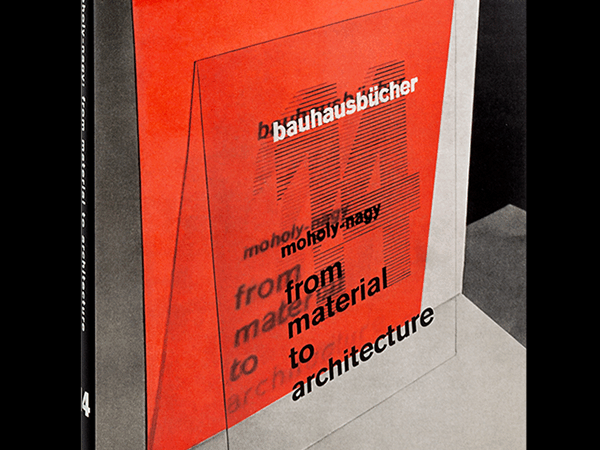

TXL. Berlin Tegel Airport, new from Park Books, traces the construction of this iconic structure from its genesis to its post-functional afterlife. The book embraces the bold visual beauty of Tegel’s structures, signage, and overall geometrical concept while also amply covering more nuanced matters of historical and architectural contexts. Visually, the book makes a powerful first impression, with its vivid front cover, spine, and back cover in yellow, green, and red respectively. The colors directly reference the chromatic wayfinding system employed by the airport: yellow and green were used for primary and secondary signage respectively, and the channels, deplaning hubs, and extendable gates that wrapped the terminal like a chunky 1970s belt were paneled in resplendent red steel that has faded to a dull crimson-brown in the decades since. Inside the covers, the book also makes a vivid impact right away, with nearly 70 pages of interior and exterior photographs of the terminal before the text even begins.

The essays that make up the book are both wide-ranging and highly focused, distilling the impossibly complex history of Cold War Berlin into its most relevant moments while examining the numerous threads of architectural history that came together at Tegel. The subsequent conversation with von Gerkan and Marg reveals new details about their process of creating such an iconic structure, which was equal parts inspired genius and quotidian diligence.

While the book starts with photos of Tegel in operation throughout the years, it ends in a surprising yet somehow perfectly fitting temporal reversal, with photos of the airport’s construction. Von Gerkan was an amateur filmmaker, documenting the entire process with his Super-8 camera, and the book includes sepia-toned stills from his hundreds of hours of recordings. The shots of a half-finished streetside terminal are poignant, with brutalist concrete surfaces still in their wooden frames and the young architects walking through the half-formed structures with broad smiles on their faces.

The Power of Six

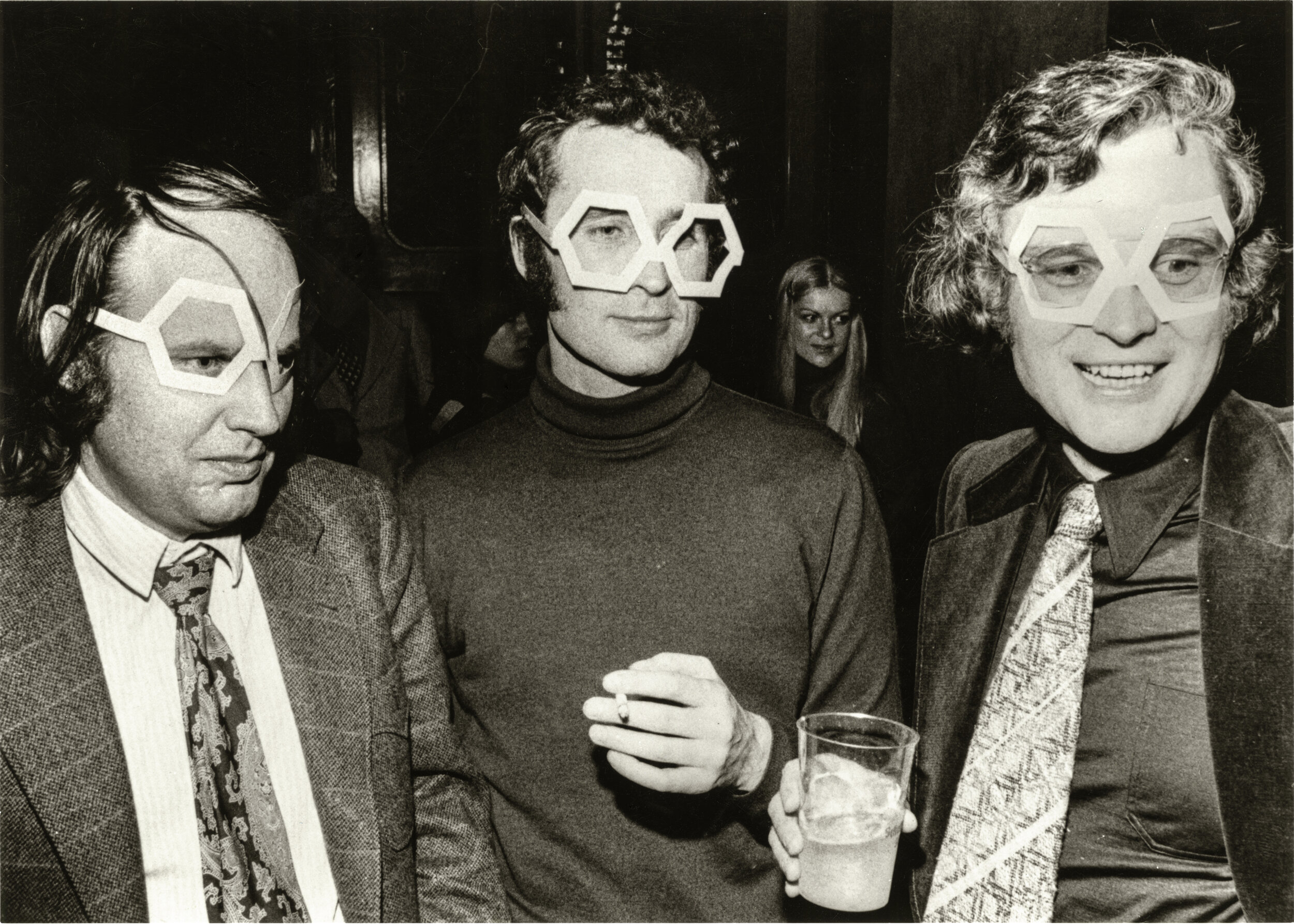

While Tegel will always be associated with hexagons – its opening party involved the handoff of an oversized hexagon-handled key, and the three architectural masterminds wearing novelty hexagon-frame glasses – von Gerkan downplays the ultimate importance of the six-sided figure:

The decisive aspect is not the hexagon, though, but that it is a closed ring. In other words, the airport could just as well have been octagonal or circular. Except that building something circular, as anyone who knows anything about construction knows, is much more expensive, because no straight parts can be used.

Still, the self-replicating nature of hexagons – particularly as they are made up of six equilateral triangles – makes them the DNA of the airport’s physical “body”. Rather than a standard square grid, the blueprints instead use a tessellation of equilateral triangles (with sides given the satisfyingly round value of 10 meters) as their basic building blocks. It is from this essential triangular unit that the project as a whole takes shape: corners form at 60- and120-degree angles, forming in places into rhombuses and hexagons, and seemingly disconnected forms hundreds of meters apart are revealed to be on the same axes. Zooming all the way out reveals this core triangle-hexagon structure at various levels of magnitude, in fractal-like outgrowths ranging from the minute (such as the individual hexagonal chairs of the main waiting area) to the brutalist monumentality of the overall structure itself.

When discussing Tegel and its design, it’s tempting to see it through a mythologized lens, a West-Berlin Cinderella story of an unknown team emerging seemingly from nowhere to create one of the world’s most iconic airports. But TXL (like the architectural team that is its subject) has done the requisite work of placing Tegel into its broader architectural continuum. The airport’s design was influenced not only by other airports (like the iconic Pan Am and TWA Terminals at JFK), but also by other West German projects such as Hans Scharoun’s sublime Berlin Philharmonic and the Munich Olympic Park, as well as more purely geometric structures like R. Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxian House and geodesic domes. Most importantly, von Gerkan and team possessed an essential savviness from the very beginning, taking Lufthansa’s own recommendations for a modern car-to-terminal-to-plane airport (now a given, but at the time fairly groundbreaking) and adapting them to the particular needs of Berlin’s new airfield.

Lifeline to the West

Tegel’s whimsical flourishes and easygoing, occasionally lounge-like feel may at first blush appear to have been blissfully unaware of the gray Cold War drabness surrounding it, but as the book points out, the airport owed its very existence to the balance between world powers (in this case the French protecting power) and their desire to maintain a hold on the city: “In retrospect,” the central essay plainly sets forth, “it is easy to forget that Tegel was a child of Berlin’s division and of its status under the four Allied powers.” The iconic, sharp-angled tower itself was under the control of the French government until reunification, and, poignantly, the very last plane to take off from the airport on November 8, 2020 was an Air France flight, bookending the airline’s storied history at the site. (Air France’s iconic Concorde even paid several visits during the 1970s and 1980s, offering the highly photogenic spectacle of supersonic curves juxtaposed against Tegel’s jutting angles.)

As accessible as the airport was by car or bus (though the lack of train connection was a constant issue), the journey once in the air was decidedly more complex: planes traveling from Berlin over GDR airspace were limited to a mere three corridors (toward Hamburg, Hannover, or Frankfurt) at strictly controlled altitudes, often resulting in bumpy flights that took much longer than equivalent stretches in other parts of Europe. But for many, including Volkwin Marg himself, who had fled the East during his student years, air travel was an indispensable way to avoid the harrowing journey through the East: “Anyone who, as a ‘deserter from the republic’ with a refugee identity card C, feared arrest along the so-called interzonal corridor, preferred not to risk traveling through the GDR by train or car at that time.” Even for those who had less to fear traveling through the GDR, the numerous checkpoints made for, at best, a tedious journey via the land route.

An Uncertain Afterlife

Tegel should have either lived forever, ideally with its ever-overdue second hexagonal ring, or been given a more graceful end. As it happened, the delays that beset the notoriously cursed BER Airport for over a decade forced Tegel into a sort of undying drudgery, where any whimsy and convenience was buried in a flood of passengers that at its peak reached ten times the airport’s intended capacity. The security procedures required for air travel in the 21st century were not kind to an airport built for effortless travel from car to terminal to plane, and between limited operational hours (negotiated month after month with increasingly impatient neighbors) and a global pandemic, Tegel in its final months could sometimes give the impression of being abandoned while still operational.

As of November 8, 2020, Tegel has been downgraded to “emergency overflow only” status for a final six months as BER gets up and running. But while its days as a functioning international airport are no more, its final run lives on in scores of overwhelmingly negative online reviews. “For 20 years I have been in different airports around the world, Berlin Tegel is by far the WORST,” says one from just a month before it closed. “In my small hometown it is so much better and this is an airport from the capital of the most rich and powerful country in Europe.” Surely many amenities in Berlin, a notoriously prickly city, have similar reviews (not least being Schönefeld, which most would agree upon as Berlin’s perennial last-place airport), but there was no denying that Tegel had become a shadow of its former self. At-gate security checkpoints sent long, unmoving lines into the sacred inner hexagon, and once inside the gate there was no returning to the land of food and coffee, even when a flight was delayed for hours.

In the airport’s final weeks, though, it saw an influx of visitors who were there simply to visit the building. Free of the stress of security checkpoints and arguments over baggage, the whimsy and playfulness of the site began to shine through once again. The “Ess-Bahn” (“eat-train”) currywurst stand remained open, and the longest security lines were for those looking to visit the terminal’s rooftop terrace to take in the full 360-degree view. On the airport’s final night in operation, hundreds of employees gathered on the darkened runway and spelled out “TXL” with flashlights in a poignant farewell. Berlin had finally broken up with Tegel, but it suddenly wasn’t ready to let it go.

The site’s future is uncertain, but it looks like it will avoid the ignominious full-demo fate of other modernist Cold War cohorts such as the Palast der Republik and Ahornblatt restaurant. Numerous proposals for the continued use of the shuttered airport have been floated. As with the nearby Siemensstadt district, which is also slated for a city-sponsored revitalization over the coming decade, the vision for TXL is that of a future-minded, curated “neighborhood” – though who would make the trip out past the Spandau Shipping Canal to simply hang out in an abandoned airport remains to be seen.

Concept art for the future TXL project shows a pan-economic blend of families, students, businesspeople, and tourists in a utopian, car-free “mixed-use” space. Berliners have been burned with countless promises of community-centered spaces that end up simply as malls, from the glass towers of Potsdamer Platz to the dull anytown brick of the Schultheissquartier to the oft-maligned Mall of Berlin. In its tech-centric pitch, the post-airport TXL project appears poised to be a similar disappointment, less a neighborhood than a business park – particularly given its fundamentally out-of-the-way location. But between its newly minted status as a protected monument (acquired in 2019) and its still-alluring architecture, Tegel may still have some surprises in it yet.

While Meinhard von Gerkan is understandably proud of his and his cohorts’ accomplishment with Tegel, he maintains a somewhat zen-like distance from discussions of the structure as a modernist icon:

The most important insight that came to mind before even getting started was that an airport does not describe a condition. It represents a useful entity that is constantly adapting to changing conditions. Therefore, things should not manifest themselves too strongly.

It’s a somewhat surprising insight, given the bold geometry and vivid colors for which Tegel is known, but one that goes a long way toward explaining the longevity and ongoing relevance of both the airport itself and the architects who created it.