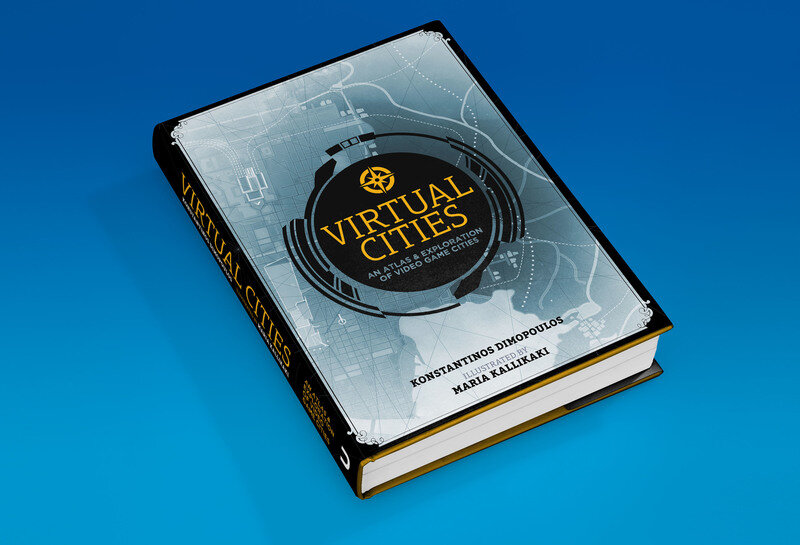

Virtual Cities

Konstantinos Dimopoulis, illus. Maria Kallikaki

€ 30, Hardcover, 255 pages

IN THE ERA before the world was fully mapped onto its current grid, creators of atlases had creative license to fill in gaps in the collective knowledge however they saw fit, with sensationalized descriptions of new lands, people, and creatures being the norm rather than the exception. With every corner of the world mapped and measured, what atlases and travel writing have gained in knowledge and accuracy they have lost, at least to some degree, in wonder and creativity.

The mapping of videogame worlds has followed a similar course, though one compressed into decades rather than millennia: the first text-based games often required players to draw maps by hand to have any hope of finding their way through worlds represented by dark screens of text, and while the first point-and-click adventure games offered more visual clues, they rarely had in-game maps – and often they were less about exploration than the particular alchemy of combining the correct objects to advance through often-absurd game worlds.

Early graphics-based RPGs like the Ultima and Final Fantasy series had “overworld” views, where the player navigated between instanced towns, dungeons, and spontaneous enemy encounters on a 2-dimensional map-like surface. With the 1990s, arguably the golden age of computer RPGs with classics like Planescape, Shadowrun, Fallout and Baldur’s Gate, ingame world and region maps became standard, and the advent of newsgroups and the World Wide Web made for an increasingly crowdsourced navigation of game worlds. The process accelerated in the new millenium, and with the rise of YouTube, any player hopelessly lost in a game world was just a quick web search away from a full video walkthrough. Exponential advances in graphics capabilities have rendered open-world games set in our world into reasonably believable simulacra of the cities they represent, to the point that someone who knows a given city well enough might even have a reasonable advantage in the mimicked game-version.

Antescher, the eldritch abandoned city in which Ant Attack (1983) takes place. All illustrations © Konstantinos Dimopoulos / Maria Kallikaki.

Virtual Cities groups its chosen game worlds under broad thematic categories (Fantasy Cities, Familiar Cities, Future Cities) and relegates release date, platform, publisher and genre to secondary information – a significant, if not revolutionary, step. Much more radically, though, and especially for a full-color, large-format book about games, there is not a single screenshot or photograph anywhere in the book’s 255 pages. Instead, illustrator Maria Kallikaki has recreated each respective game world through hand-drawn illustrations, including the maps of game cities, which have been re-envisioned in a wild assortment of styles, each reflecting the particular mood and aesthetic of the city portrayed. Grim Fandango‘s Rubacava uses a dark color palette and Art Deco typeface that match its stylish neo-noir necropolis setting, while the western city of Lizard Breath (It Came From the Desert) uses a cowboy-themed slab serif on a yellowed, tattered-edged sheet. Similarly, her renderings of various virtual urban settings, rather than copying notable in-game moments, are instead drawn from imagined perspectives that are more evocative than directly representative of the game experience. The overall effect is a welcome defamiliarization, particularly for anyone who knows every pixel of any of the featured game worlds by heart.

The text follows a similar approach, eschewing the player perspective in favor of an in-world one, which the book’s introduction suggests could be “a geographer perhaps, a chronicler, or someone writing a tourist guide” – in short, “a fictional local surveyor.” The descriptions avoid referencing specific game characters (extending even to their respective protagonists), instead focusing on how each particular city reflects on the greater game world. Many of these analyses place a refreshing emphasis on real-world urban issues like class disparity and environmental degradation, again via an in-world perspective that supports, rather than distracts from, each game’s world-building efforts.

Most entries include “Design Insights” sections with interviews and analysis that shed light on the development process. These texts play a secondary role to the ingame perspectives that precede them, but nonetheless contain some of the book’s most striking writing: the phantasmagoric gothic steeples of Yharnam (Bloodborne) convey “the vertigo of the sublime in its civic form”, while Resident Evil’s Raccoon City is “an intriguingly skewed vision of American Midwestern American urbanism crafted by Japanese game developers using late 1990s technology under the influence of 1970s and 1980s zombie movies.”

The intermingling of games from different eras, in particular, serves as an equalizing approach. It means a game’s setting can be explored and analyzed independent of any limitations imposed by the technology of its time; early game cities like Antescher (Ant Attack, 1983) and Rockvil (A Mind Forever Voyaging, 1985) receive the same rigorous scrutiny as those from the 2010s, giving the overall impression of a continuum of like-minded developers working toward a common goal over decades.

We asked the author about his unique approach to game writing, his history with games, and what the future of digital cities might be.

In the book, you describe each city from the perspective of someone within the game world. Did writing about each game using its own internal logic make the process more difficult, or was it somehow freeing?

I would say it was both more difficult and more freeing. It took a while for me to be able to imagine each individual city as a whole and to paint a convincing, legible picture in my mind, but after things finally clicked, writing was a truly joyful experience. Besides, roughly imagining the character who would be narrating and describing the goings-on and geographies, and trying to understand their target audience, was a very playful writing exercise.

City 17, the dystopian police-state metropolis in which Half-Life 2 begins.

Of course some information had to be omitted or merely alluded to, a specific point in time had to be chosen for each in-world approach, and lots of implied, granular detail had to be filled in. But this all actually helped me recreate that feeling of old atlases, and the incomplete, subjective descriptions by 19th century travelers. Or at least I think it helped.

What’s more, the in-world approach allowed me to further flesh out places that were interesting backgrounds and not much else into living, breathing entities I found satisfying, and to occasionally even subtly critique the described city.

Deciding which cities and games to leave out of the book must have been a difficult process. What were some of your favorites that didn’t quite make the cut?

It was indeed difficult, and many beloved places had to be left out, as balancing the contents to cover all genres, systems, and eras was a decision that came with very specific demands. Some of the cities that didn’t make it, but would absolutely have to be part of a second Virtual Cities volume, include the cyberpunk Neo Kobe City from Snatcher, the modernist City of Glass from Mirror’s Edge, Ultima VII’s detailed fantasy town of Britain, the dynamic civic worlds of the Gothic RPGs, the colorful city of Crazy Taxi, Baldur’s Gate, one of the Quest for Glory towns, and, if possible, Paragon City from City of Heroes.

I would also include virtual cities that were published just as the atlas was being edited: Revachol from Disco Elysium would be a prime candidate, as I already adore this place.

What were some of the games that made strong early impressions on you? If you had to choose an all-time favorite, what would it be?

The atmospheric New Orleans of Gabriel Knight.

I am almost certain that the very first game I actually played was Berzerk on my cousins’ Atari 2600. I must have been four or five at the time, and thoroughly impressed by being able to make things on the TV move. I was also terrified of Evil Otto whom we used to call the Boogeyman.

The variety of 8-bit computer games that followed were interesting but never overshadowed actual toys. Eventually though I graduated to the 16-bit era, the 1990s, and the rise of the RPG and adventure genres. Those story- and puzzle-heavy games with their rich worlds, exotic situations, and utterly strange characters left a lasting impression on me, and I still consider them my favorite types of video game.

Games like The Secret of Monkey Island with its playful and engrossing pirate setting, lushly animated text adventure Wonderland, and classic dungeon crawler Eye of the Beholder are still experiences I vividly remember loving as a kid, even if Lucasarts’ Monkey Island 2, Sierra’s Space Quest IV and Dynamix’s Willy Beamish are the three games I have attached some of my fondest childhood memories to. If I had to name an all-time favorite it would be Monkey Island 2: LeChuck’s Revenge. It is an essentially perfect game.

Gabriel Knight’s city map appears over a watercolored rendering of the greater Lake Pontchartrain area.

What other projects are on the horizon?

I am already working on a new, completely different book I cannot quite comment on just yet. I recently published the Ex Novo city-building board game / RPG hybrid with Martin Nerurkar, and am currently wrapping up work on the cities of two projects (one video game and one tabletop RPG), while writing for Wireframe magazine and lecturing on level design at SAE Athens. What’s more, the possibilities for a Virtual Cities 2 are being looked into, the indie game Lake (which features some of my work) is about to be released, and I am polishing up the final design for a board game I’m creating with an artist friend.

Lastly, while a traditional view would call spending time in virtual worlds escapism, do you see these spaces as possibly gaining a newfound respectability in a post-pandemic world?

To begin with, I’d say it seems escapism, both virtual and alcohol/drug-induced, has been really big during this pandemic. So far the statistics have been impressive, and certainly understandable.

Virtual cities in particular have given us ways to engage with often exotic types of urbanism, and partially re-live the civic experience that has for the most part been taken away. Besides, art has often served as humanity’s comforter during difficult times, though not exclusively via the route of escapism. Honestly, I never see games only as a means to escape our reality. They and their environments can be (and often are) meaningful in all the ways art is. They can be thought-provoking, they can be subversive or sublime, they can carry beauty and emotion, and they never fail to convey political ideas, even if rudimentary.

Rubacava, a surprisingly lively “city of the dead” (Grim Fandango, 1998).

Admittedly I’m having a hard time imagining a post-pandemic world right now, especially as the Western world is doing a spectacular work of messing up its response to the virus, but honestly I cannot imagine things being too different from the pre-pandemic world. With the exception of large-scale social unrest. I suppose, but I am not certain as to what the role of virtual (or game) cities and entertainment in general will be in this scenario. Pandemic aside, I do feel that the spaces of games are rising in prominence anyway, which I can only see as something positive.

You can read more about Konstantinos Dimopoulos on his website. Virtual Cities is available from Bookshop.org (Europe), W.W. Norton (US), and as an Ebook on Unbound.