DURING ITS FOUR-plus decades of existence, the GDR was a unique geopolitical paradox. Its place at the heart of the Cold War conflict belied the simple, day-to-day lives of the vast majority of its citizens. This paradox manifests itself visibly in the architecture of the former GDR, where often-cosmic abstract and geometric tendencies exist alongside the drab and mundane. These divergent tendencies inform the architecture of numerous post-Communist countries, but in the GDR (and particularly Berlin, the East-West split in microcosm) they were often amplified by historical factors.

Coastguard tower, Binz. All photos © Prestel Publishing / Hans Engels

First and foremost, the massive postwar rebuilding needed in the GDR meant that it often served as a showpiece for leading Soviet trends. Berlin’s almost completely destroyed Große Frankfurter Straße was rechristened Stalinallee post-war, and built up in the anachronistic neoclassical style favored by its namesake. The Fernsehturm on Alexanderplatz was built to see (and be seen by) the city’s Western sectors, while cultural and arts centers sprang up from Dresden to Magdeburg to Rostock.

Interhotel Panorama, Oberhof

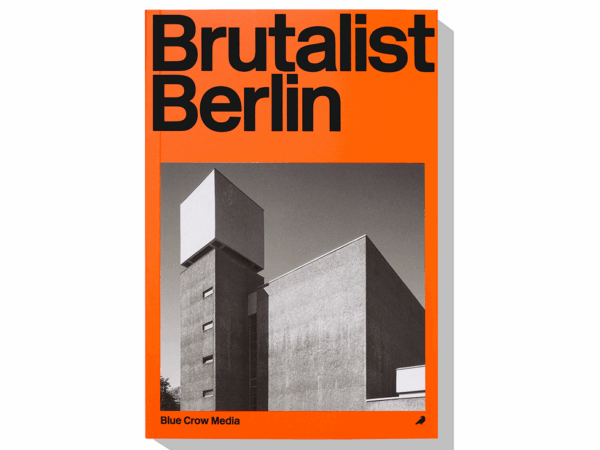

East German Modern features Hans Engels’ mostly current photographs of buildings from throughout the former GDR, accompanied by an introductory essay that poses a boldly straightforward question about the preservation of East German architecture:

What could be beautiful about the buildings of a dictatorship?

Panorama restaurant, Schwerin

It’s a refreshingly candid question that cuts to the heart of “Ostalgie” (as well as the fetishization of Brutalism and Soviet architecture) in the 21st century. The essay goes on to break down the (in retrospect, brief) history of the GDR into five loose architectural eras: “Reconstruction”, “Stalinist baroque clacissism”, “International Modernism”, “Prefab / Plattenbau”, and “End of GDR, industrial efficiency, and revalorization of original styles”. This breakdown provides an effective framework for thinking about GDR-era buildings, and offers those unfamiliar with the nuances of East German architecture a way into an often bewildering subject.

Bus station, Chemnitz

Engels’ photographs are beautifully reproduced in large-format matte prints, with a maximum of one photo per page and many taking up both sides of a double-page spread. The book eschews the otherworldly, black-and-white style of some post-Soviet architecture collections, instead opting for straightforward, mostly frontal whole-building shots. Brutalism and Cold War fetishists may be disappointed with the sunlit, full-color aesthetic, but the catalog-like approach fits well with a book whose intent reaches beyond architectural appreciation to nothing less than a reconciliation between East and West.

East German Modern

Hans Engels

Prestel Publishing

$50 / £35