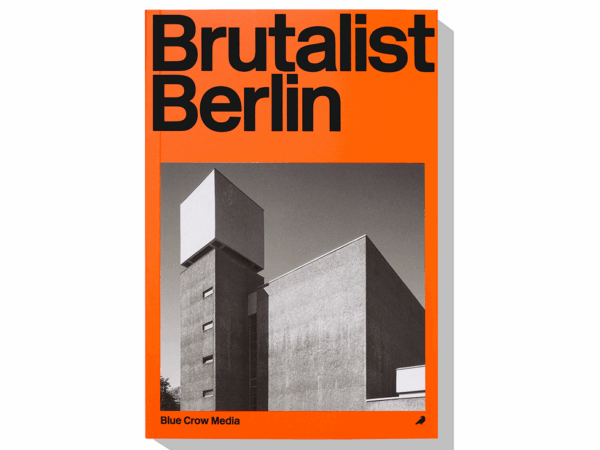

Soviet Modernism, Brutalism, Post-Modernism: Buildings and Structures in Ukraine 1955-1991

Ievgeniia Gubkina (text), Alex Bykov (photos)

Osnovy Publishing

Hardcover, 264 pages, $80

THERE ARE FEW European architectural legacies more fraught than that of Soviet-era structures in the former USSR, and few places where this legacy is more divisive than Ukraine. In the decades since the dissolution of the USSR, Ukraine’s Soviet past – which, even apart from the devastation wrought by the Nazis, includes tragedies such as Stalin’s genocidal holodomor and the Chernobyl disaster – has remained a wound that refuses to heal. More recently, Russia’s 2014 annexation/occupation of Crimea and Donbass further inflamed tensions between Kyiv and Moscow, and ensured the debate over the Soviet legacy in Ukraine would be poisoned for years to come.

Druzhba Sanatorium, Crimea. All photos © Alex Bykov / Osnovy Publishing.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Cold War-era architecture in Ukraine has become an ongoing casualty in the attempt to decouple the country from its Soviet past. Under a policy of “de-Sovietization”, countless structures, from monumental housing and office blocks to modest sculptures and murals, have been razed over the past decades (explored in more detail in our article on Chernobyl: A Stalker’s Guide). The value of Brutalist architecture is a contentious subject even in countries far to the west of the Iron Curtain; in Ukraine the subject is politicized to the point that objective discussion is all but impossible.

Osnovy Publishing’s Soviet Modernism, Brutalism, Post-Modernism enters this debate head-on, making a strong argument not only for the recategorization of Ukrainian Soviet architecture into more meaningful subcategories, but also for its ongoing preservation and revitalization. Kharkiv-based author Ievgeniia Gubkina has studied and written about Ukrainian architectural history extensively, and sets the framework for a bold re-envisioning of the country’s Cold War-era architecture. Rather than downplaying the dark and difficult legacy of the Soviet era in modern Ukraine, she confronts it head-on for what it was: a dictatorship where architectural trends were dictated by a governing body that was both unbending and fickle.

Hotel Salute, Kyiv

In both its introductory text and its refreshingly unromanticized photographs (by Kiev-based photographer Alex Bykov), the book seeks to re-examine Soviet architecture in Ukraine via a new framework, bringing the discussion back from the brink of its hopelessly politicized state. Not that the book avoids politics: Gubkina holds both the Soviet government and the newly global-capitalist system of post-1990 Ukraine to account for their decisions. She makes an uncomfortable point that is too often lacking in architectural studies: namely, that buildings are an expensive endeavor that requires a client, be it the USSR pre-1990s or the private companies and investors that followed.

The book goes well beyond the usual designation of all Soviet-era structures as “Modernist”, and instead breaks Soviet Ukraine’s architecture into three overarching categories: Modernism, Brutalism, and Post-Modernism. This more nuanced breakdown allows the book to include many structures that reflect the reality of 20th century architecture that fall well outside the Brutalism-porn oddities at the heart of some photo collections. That’s not to say there aren’t plenty of monumental raw-concrete oddities in the book; as a relatively complete collection of Soviet architecture in Ukraine, it includes well-known Brutalist structures such as the Kyiv Memory Park and the Druzhba Sanatorium, the latter of which was featured on the cover of Frédéric Chaubin’s CCCP.

Memory Park and Crematory, Kyiv

The first section, Modernism, applies more stringent standards than the phrase usually warrants, specifically examining structures built during the post-Stalinist “thaw” that saw Ukrainian architects freed from the stifling Neoclassical requirements in place until the mid-1950s. Gubkina rightfully designates Western Modernism as a primarily aesthetic movement (as opposed to a utopian or social one), meaning its socialist “retrofitting” is a fraught process that mostly results in a more limited range of techniques. Still, in a country as large and with such varied local governments as Ukraine, it’s no surprise numerous oddities and outstanding examples were built – and despite the de-Sovietization movement, many (particularly those that are indispensable for local infrastructures such as bus and train stations) have remained in continual use.

The Brutalism section likewise takes a refreshingly critical view of the country’s Soviet-era raw-concrete bulwarks, deflating the concrete balloon somewhat by pointing out that many “Brutalist” buildings actually used insubstantial concrete cladding over underlying brick structures, which were in some cases simply cheaper and easier to build. While this foregrounding of Socialist aesthetics over practical considerations doesn’t fully negate the utopian potential of Brutalist architecture, it’s an important and undervalued point in many studies of Soviet architecture, and is a further example of the clear-eyed view the book has of the realities of 20th century architecture. Nonetheless, the book offers such a complete survey of the country’s buildings that anyone hungry for monumental concrete will not be disappointed.

Soniachna Metrotram Station

The third and final section, Post-Modernism, is in some ways the book’s most interesting. As Gubkina argues, Soviet Post-Modernism was something of a “lightning in a bottle” moment: it aspired to the freedom enjoyed by international architecture toward the end of the 20th century, but was paradoxically killed at the moment it achieved its actual freedom with the dissolution of the Soviet empire and the transition to global capitalism. Ironically, this moment saw an inversion of Soviet Post-Modernism to the “mere aesthetics” of Western Modernism decades prior:

…in the discourse of Soviet Post-Modernism we are unlikely to find ethical or political themes that match political and social issues in the discourse of Western-European Post-Modernism of that period. Soviet Post-Modernism talks only about aesthetics. Choosing between ethics and aesthetics, it seeks salvation in aesthetic utopias, whilst remaining blind to social and political problems.

While it’s a somewhat harsh assessment of the motivations and trends of the era, it nonetheless allows the book to include an expanded repertoire of buildings that would otherwise fall outside a more standard survey of Modernist or Brutalist architecture. Many of the structures in this section feature an expanded range of materials such as three-dimensional metal patterns, brick, and colored tiles.

The striking Kyiv Institute of Cybernetics, an example of a postmodernist structure that retains the raw concrete and geometric monumentality of earlier Brutalist architecture.

Ultimately, the book’s greatest appeal is its inclusion of structures that would lie outside most surveys of Modernist Soviet architecture. Bykov’s photos eschew close zooms and forced perspectives, and are content to show the broader urban contexts in which the buildings are situated, including construction, cars, and, most refreshingly, people going about their daily business. This human element is essential to the book’s strongest argument for preservation of Soviet-era structures: that they are not only part of a historical continuum, but also of living cities. Just as they do not exist in a historical vacuum, their removal would be a blow not only to Ukraine’s architectural history, but in many cases to its day-to-day life.