THE 67TH BERLINALE FEATURES a wide-ranging selection of curiosities from past decades, from thwarted epics to camp relics to vast, inscrutable multi-reel psychedelia—and even in such an especially strong year for uncompromisingly strange films with singular artistic visions, a few managed to stand out from the crowd.

ON THE SILVER GLOBE (1977/1988)

While Andzrej Żuławski is best-known for Possession, his Berlin-filmed blast of body-horror psychodrama starring Sam Neill and Isabelle Adjani, the unfinished sci-fi epic On the Silver Globe (Na srebrnym globie) somehow manages to eclipse even that notorious film in scope, transgressiveness, and intensity. The film tells the story of a space exploration expedition that lands on a strange and hostile planet, based on a novel by Żuławski’s great-uncle. Filming began during a relative thaw in Polish state censorship; set on two planets, the production used an incredible range of filming locations (including Crimea, the Gobi Desert, and the Wieliczka Salt Mine in Poland) as backdrops, coupled with heavy lens filters that give a silver-blue cast to many of the shots.

The costumes, particularly those of the genuinely frightening “bird people”, transcend any vestiges of campiness with their commitment to the overarching vision of a dark futurist tribalism. Vivid colors often manage to break through the silvery filters in many set pieces, evoking Hammer and Shaw Brothers films of the era such as Demons of the Mind and Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires and adding some welcome color to the monochrome bleakness.

The 1977 rise of the conservative Janusz Wilhelmi as head of the ministry of cultural affairs saw the production abruptly halted, and the sets and costumes completely destroyed in a tragic act of artistic repression. Żuławski returned to his adopted home of France and abandoned the project for the next decade while he made other films, including Possession. He returned to the project in the 80s, eventually completing it—in the sense that he assembled the existing reels and produced new footage (mostly consisting of landscape shots and his own voiceover) to fill in gaps in the story. Even in its fragmented form, it’s a towering achievement, and a truly atmospheric and dread-inducing vision.

ORG (1967-1978)

Unlike On the Silver Globe, production on Fernando Birri’s experimental epic was never interrupted—it simply took 11 years to complete. This anti-film uses over 26,000 cuts (all of which had to be done by hand with scissors and tape), at times reaching hundreds of cuts within a single “shot”. The result truly tests of the limits of narrative: what makes sense on a scale of seconds evaporates after minutes or hours, while the broader hours-long arc (based loosely on a story by Thomas Mann, itself based on an Indian legend) is constantly thwarted by the unending fusillade of twitching audio and visual data pouring from the screen.

The film stars the Italian-German actor Terence Hill, who at the time of filming was a rising star of more standard genre fare, particularly Westerns. While incredibly beautiful at times (especially during the first half of its three-plus-hour run time, which focuses on its trio of undeniably attractive and dynamic leading actors), it nonetheless becomes a slog during its second half—particularly during minutes-long stretches of alternating noise-squalls and silence over a black screen.

It’s a film that almost demands the substance-based pairings that often accompany heavily experimental psychedelia; for those looking to enjoy it sober, the film might better convey its gem-like moments of startling beauty in a more unconventional setting such as a multi-room installation or an outdoor park. This is not a roundabout way of reducing the film to a curiosity: on the contrary, it should play to an audience that is as free from constraints and boundaries as the film itself—but as a single, unbroken experience, it’s certainly one of arthouse cinema’s more grueling marathons.

KAMIKAZE 1989 (1982)

The visuals of Wolf Gremm’s West-German cyberpunk curiosity Kamikaze 1989 alone are enough to make it worthwhile viewing for cult film fans. The unexpectedly strong performance of Rainer Werner Fassbinder (known for directing vastly superior films in the same vein, particularly World on a Wire), however, gives a surprising depth to the character of Lieutenant Jansen, who is tasked with solving a case of murder and corporate espionage in a retro-future-camp version of West Germany.

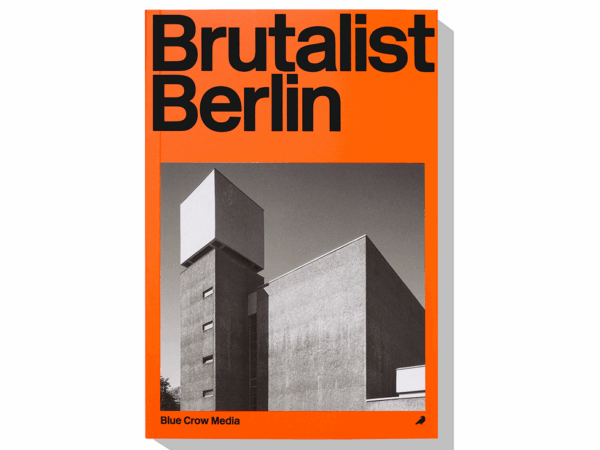

Based on Per Wahlöö’s 1964 novel Murder on the Thirty-First Floor and set in a quasi-futurist dystopia where unhappiness and troubling dreams have been eradicated, it’s a shoestring-cyberpunk Dick Tracy filtered through the camp futurism of The Apple. The film uses the curious postwar architecture of the Federal German Republic to full effect, particularly the office building that serves as the central focus of the film’s action. Its curiosities also include a wide array of vehicular outliers that range from motorized tricycles to graffiti-covered cars to ambulances that transport patients for mandatory “happiness conditioning”.

The vision of Kamikaze 1989 is bolstered by a remarkable soundtrack from Tangerine Dream, which balances the visual campiness with some geniuinely great tracks. And while the visuals are squarely camp, the griminess of the Federal Republic in the 1980s shines through, infusing the garish colors with gray concrete and flat-fronted Plattenbauen. One of the more effective visual elements, skirting the line between camp and effective dystopian set piece, is the array of video screens that glow from elevators, cars, and the police gym/roller disco where Lieutenant Jansen unwinds, alternately broadcasting police orders and a “laughing contest” (complete with corporate sponsors) that lasts the duration of the film.

Accompanying both the Berlinale’s showing and the DVD edition of the film are John Cassavetes’ unhinged radio ads for its original release, in which he (perhaps drunkenly) rants about Fassbinder’s corpulent figure and maniacally praises the ubiquitous leopard pattern that bedecks everything in the film, from Jansen’s suits to his revolver to his car’s upholstery.

ROPACI / THE OIL GOBBLERS (1988)

This 20-minute faux documentary, made in the final years of communist Czechoslovakia, follows a crew of scientists in search of the “Ropáci”, a previously-unknown species discovered in the toxic oil fields of northern Bohemia. The creatures themselves are brought lovingly to life with a variety of rubbery practical models, including both adult and baby puppet versions, as well as full specimens that sit forlornly on cliffsides and drainage pipes in hilarious repose against the backdrop of a genuinely bleak, and very real, industrial wasteland.

Add in a score laden with synthesizers and soaring saxophones, and the result comes in somewhere between Jan Švankmajer and the “2051 A.D.” intro to Strange Brew: a darkly absurdist film that falls just on the side of whimsy. It helps that there’s plenty of humor sprinkled throughout, though the darkly comedic final message—that rare as the Ropáci may be, they’re sure to thrive in an increasingly polluted future—dampens the mood somewhat given its undeniable accuracy.

This year’s Berlinale Retrospective features numerous rarer speculative films, including a strong selection from the former Soviet bloc. A partial list is below; visit the official Berlinale site for more info.

- The War of the Worlds (USA, 1953)

- Ikarie XB1 (Czechoslovakia, 1964)

- GOG (USA, 1954, in 3D)

- Eolomea (East Germany, 1972)

- Seconds (USA, 1966)

- World on a Wire (West Germany, 1973)

- Test Pilota Pirxa (Poland/USSR)

- On the Beach (USA, 1959)

- Warning From Space (Japan, 1956)

- 1984 (UK/USA, 1956)

- THX 1138 (USA, 1971)

- A Trip to Mars (Denmark, 1918)

- Algol, Tragedy of Power (Germany, 1920)

- A Day After a Hundred Years (Japan, 1933)

- O-bi, O-ba: The End of Civilization (Poland, 1985)

- Letters From a Dead Man (USSR, 1986)